Shivani Singh, the South Asia co-community organiser for Remake, has long been an advocate for sustainability. ‘I always wanted that personal touch to everything I wore, something that has empowered at least a few people along the way,’ says Shivani. And, her wedding wasn’t any different. ‘The common perception is that it is almost impossible to have a completely sustainable wedding and follow the traditions,’ she says. But with a little grit and imagination, she was able to put in practice what she preaches.

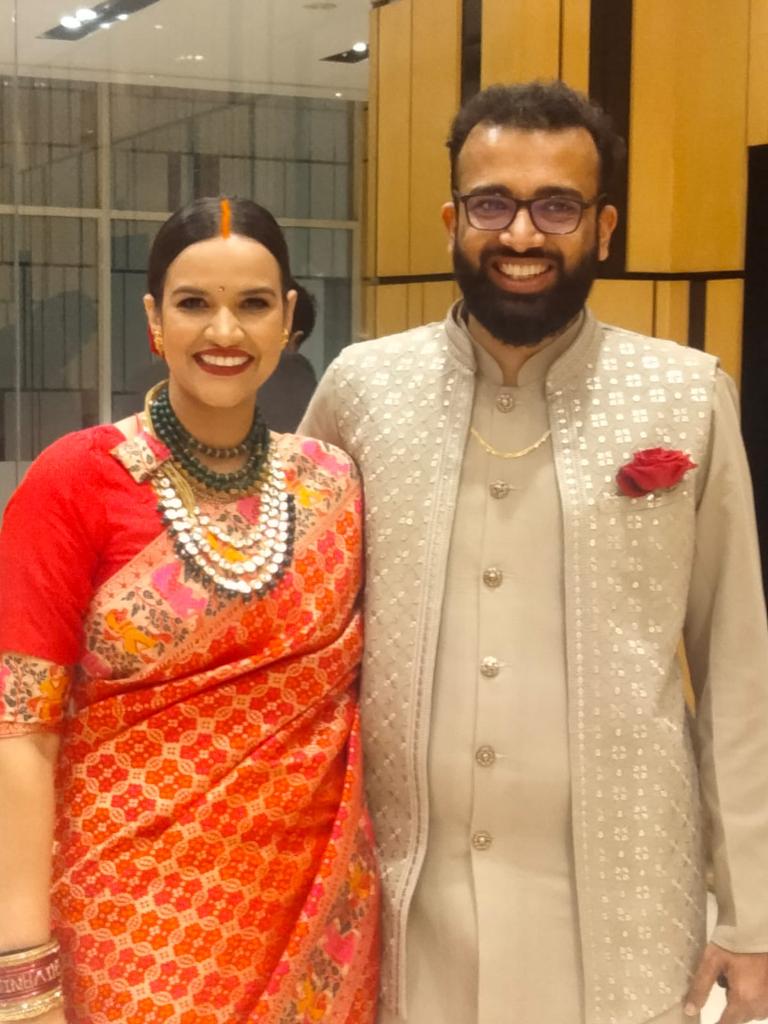

Shivani Singh got married in Ranchi earlier this year, and her wedding is a sustainable fairy tale. ‘Like they say, you dress like the person you want to become–it rings true for me,’ says Shivani, who put in hours of research, gathered online references… all so she could fulfil her wedding dreams while being mindful. And, she did most of her wedding shopping online… We know it sounds surreal! No multiple trips to Chandni Chowk and Jaipur. And no fancy designer labels. Her trousseau consisted of all things traditional, but everything from clothes to the spices were sourced consciously. ‘I wanted to stay true to my roots as well as live up to my bridal desires,’ Shivani says. Here’s how you can, too.

‘Communication is key.’

‘You need to discuss your wedding intentions openly with your family members,’ advises Shivani. ‘But, first you need to be sure of exactly what you want.’ She feels that when it comes to wedding conversations with family, you will never be let down. ‘Open up to them and they will help you fight your battles,’ she says. Even when it came to her friends, Shivani insisted they only gift her traditional pieces or heirlooms. However, the usual tug and pull between the two families is inescapable at Indian weddings. ‘Each of the families wants an upper hand,’ she says. ‘Ours was the first inter-caste marriage in both our families, so the stakes were high.’ Coming from different regions too, the rituals and customs were all different but both the families were able to arrive at common ground by deciding on a few common rituals.

‘Do your research.’

‘Where there is a will, there is a way,’ says Shivani. She spent the 3-4 months leading up to the wedding doing her research, on possible vendors and manufacturers she could turn to. ‘I was in constant touch with them,’ she says. ‘I would even regularly ask them to send in pictures.’ It can seem like a daunting task. However, she emphasises that it’s well worth the effort. Shivani used Indiamart, especially for her bulk purchases, such as gifts for friends and family. ‘I presented myself as a serious buyer, so they were more than willing to share pictures,’ she says. She even managed to get a customised Madhubani sari with her and her husband’s names printed on it. ‘My husband is still amazed I managed to pull this off,’ she smiles.

‘Pay attention to purity and quality.’

Since Shivani was so focussed on traditional clothing and craft-based garments, purity and quality were a major factor. For years, she did not buy any clothing item for herself but being so heavily invested in sustainability, she had a keen eye. ‘It’s almost how a child can identify a toy that he’s been eyeing from a distance,’ she says. ‘It’s the same for me with clothes and fabrics’. She can even identify from a picture if the fabric is fake or not. ‘In fact, I am now able to differentiate between the jaalis of the different kinds of Benarasis, to judge authenticity,’ she exclaims.

‘Work your way around the system.’

When it came to certain practices, traditional clothing choices were a non-negotiable. So, Shivani found her way around it. For example, a ritual called sawa mahina (one month and a half), which is quite prominent in her family and demands the bride wears a new item of clothing for the first 45 days, post the wedding. ‘My mom was adamant that I follow this ritual for my trousseau,’ she says. ‘There was no way around it.’ However, Shivani made sure these items were quality, handloom fabrics and were sourced mindfully. ‘I even upcycled a few garments out of my mother’s and mother-in-law’s saris, and used unstitched fabric lying around the house,’ she adds. ‘I clearly knew I didn’t want to compromise with the quality.’

‘Find your priorities.’

For the main ceremony, Shivani wanted to wear a lehenga, but her mom insisted she wear the traditional yellow sari for the wachan (vows) ceremony, commonly known as the pheras. So Shivani went with both. She wore a lehenga for the varamala (garland exchange) and changed into a yellow sari for the wachan. ‘I knew I didn’t want machine-made,’ she says. ‘So my lehenga, which was inspired by my mother’s, was painstakingly created–designed by my mother and me, in memory of hers, and handmade by skilled artisans.’

Wedding attires are usually a one-time wear and Shivani wanted to change that. ‘I got the colour of my blouse customised to match with other saris or lehengas in the future,’ she explains. Shivani also ensured minimal plastic waste by replacing zips and hooks with doris, wherever she could.

‘Pick local crafts wherever possible.’

While shopping for her wedding trousseau, Shivani wanted to empower as many people as possible, while also keeping it cost efficient. Her trousseau consisted of sustainably-sourced handprinted cotton, linen and georgette fabrics, and Maheshawari silk, Chanderi, Kota Doria, Ikkats, Gujarati Patola, Benarasi and Pashmina, among others. Shivani was even able to get a kurta stitched for her father through these local vendors she found online. ‘The fitting was not great so I had to get it altered but the fabric was of excellent quality,’ she says. ‘And, I know at least 2-3 people were involved and empowered in the making of the kurta.’

When it came to storing her saris, and matching potlis with her outfits, Shivani turned to the women of the Samarpan Foundation, a global volunteer-based humanitarian organisation, who crafted these products out of fabric waste. She is also a part-time volunteer at the Samarpan Foundation that empowers women through skill development and providing livelihood.

‘Be selective.’

Shivani intentionally got only a few of her blouses stitched. ‘One was definitely the cost factor and the second was the fact that my body was bound to change,’ she explains. Even for the choice of her saris, Shivani opted for quality over quantity. ‘I wanted to buy only one of each type of fabric,’ she says. She managed to get most of her quality fabrics for the trousseau at reasonable prices except a Chikankari and a zari sari. ‘I had to be selective with my choices, especially as fairly-sourced sustainable fabrics are already expensive,’ she explains. Even when it came to storage, Shivani was able to convince her relatives to hand over their saris or fabrics lying around, so she could convert them into sari bags or potlis. ‘As long as the fabrics were of good quality and were not a polyester blend, they were all welcome,’ she says.

‘Earmark your people.’

For her wedding lehenga, Shivani wanted someone to execute her vision with minimal wastage. Moving away from mainstream designers, she customized the look to make it more personal, whilst involving and empowering as many people as she could in the process.

Inspired by her mom’s bridal lehenga, she spent enough time meeting kaarigars and local tailors. ‘The most cumbersome task was explaining the lehenga design to my local tailor,’ she says. ‘It was mad, but it wasn’t maddening!’