Set in a colourful backdrop, with Bollywood’s It girl Jacqueline Fernandes setting the screen on fire, Badhshah’s Genda Phool has all the makings of a hit number. Not too long back, it was a constant feature, being blasted at weddings, festivals, parties, any celebration, anytime, anywhere. People were hooked!

But what is little known is that Badshah had, in fact, picked up the song from Ratan Kahar, an 85-year-old folk musician who had composed and first sung the song way back in 1972. And, if it weren’t for social media, Ratan Kahar would never have known that his song had been misappropriated. Many may argue that Badshah merely used the folk song as inspiration, but that would be inaccurate. So what is it that makes Badshah’s work misappropriation? And how does one tell appropriation from inspiration?

Defining Traditional Cultural Expressions

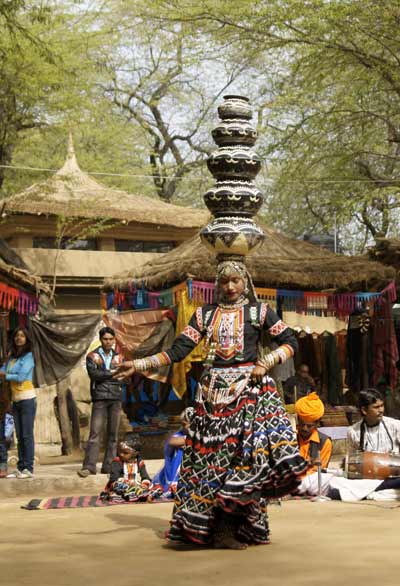

Traditional Cultural Expressions, over time, have begun to comprise of traditional writings, languages, customs, songs, paintings, handicrafts, rituals, ceremonies and medical knowledge, especially if it belongs to a community, primarily the indigenous population, or is passed down from one generation to another, even if the original author may be unknown. These expressions are adopted by the community, as and how they consider best, largely for conveying their sentiments or stories. However, due to no legal definition of what actually constitutes traditional cultural expressions, they are often appropriated for commercial as well as non-commercial reasons.

Appropriation v/s Inspiration

The line between appropriation and inspiration is very thin and sometimes appropriation may be unintentional. Yet, an individual is guilty of appropriating Traditional Cultural Expressions when they adopt an element or the entire Traditional Cultural Expression, repurpose it as a whole or in an abstract, for their own benefit, without permission or acknowledging the community to which it originally belongs.

It is a grave misunderstanding that only the West has been appropriating East’s cultural expressions. Indians have been equally, if not more, guilty of appropriating their own indigenous population’s cultural expressions without any sort of acknowledgement. At the same time, the appropriation can often be a result of ignorant attitude or a lack of awareness about the existence of cultural expressions but does not of course apply when there is a blatant copy of a Traditional Cultural Expression, much like Badshah’s “Genda Phool”. In all honesty, it was probably Badshah’s ignorant attitude, being a famous singer and rapper merged with the fact that Ratan Kahar lacked resources as well as the means to lay any claim to his song.

Similarly, there is the case of appropriation of Kantha needle work. Initially, it was started by a community of rural women in India as a medium to work as well as express their personal sentiments onto the embroidery. As it wasn’t a common sighting back in the day in rural India for women to be a part of something big, it quickly caught the eye of the handicraft industry. Slowly over time, when commercialization was at its peak, the entrepreneurs that were a part of the handicraft industry, in the nearby towns recognized a market for such work and started training other people for the work and slowly it began being mass produced. It was a straight-forward case of misappropriation but went unrecognized as needlework was never considered a Traditional Cultural Expression, but only a novel way to earn money. And, this case perfectly portrays the ignorance and appropriation of a community’s cultural expression.

Why is it important to protect the Traditional Culture Expressions of a community?

Being an essential part of Indian heritage, the misuse of these Traditional Cultural Expressions not only negatively impacts the community, but also further creates ignorance amongst us as citizens of the world. The intention behind protecting Traditional Cultural Expressions is in line with the objectives of the Intellectual Property Rights. Intellectual Property Rights or IP rights are a bundle of rights, similar to property rights but for the intellectual work one creates such as rights on an invention, on your brand name or even rights on poems. The aim is to safeguard these practices, provide the community a channel to utilise their knowledge for commercial purposes, if they wish to, and ultimately prevent appropriation and provide them a weapon for successfully enforcing their rights in case of appropriation.

It’s a given, that law alone would not be able to safeguard their practices, however, what law will definitely do is act as a deterrence tool. Currently, the issue at hand is not whether Traditional Cultural Expressions need to be protected in some manner, but whether existing intellectual property (IP) laws meet the requirement and if not, what kind of law is required. The simple answer is NO. The current IP regime is not equipped in catering to different aspects of Traditional Cultural Expressions.

Let us look at the various IP laws that ordinally protect creative arts such as songs, lyrics, choreography, or products originating from a geographical location and how they fall short of protecting the Traditional Cultural Expressions.

Copyright

The first kind of protection is the Copyright law that protects literary, artistic, and music works that are original, fixed in a tangible medium and have been created by a single author. Originality as per the judicial decisions is stated as “to the expression of creative thought and not to the thought itself”. The test for originality is that the work must originate from the author but must not be a copy, and judged only if the author has exercised skill, judgement and labor.

Given that Traditional Cultural Expressions are inherited from the ancestors, the newer generations cannot possibly meet the requirement of originality established by courts. Furthermore, since Traditional Cultural Expressions are developed by community and are possessed by a community, there is no one author. Additionally, Traditional Cultural Expressions are not always written down or fixed on a tangible medium (such as on a piece of paper), they are usually taught to future generations through word of mouth. And, copyright is only awarded for a limited time period and once the copyright expires, the work is in public domain and open for people to utilize for commercial purposes. Therefore, Traditional Cultural Expressions may not even qualify to be copyrightable and even if some of them could be, they would never own the rights on it forever.

Geographical Indication

The second type of IP right is the Geographical Indication, which intends to protect the geographical location of goods that is produced by communities in a system where in people know that the particular product comes from a specific area.

While this kind of IP seems to be a route that could address the unique nature of Traditional Cultural Expressions, in reality, Geographical Indication also has its own fall backs. Firstly, Geographical Indication is viewed as a commercial resource, and therefore, it may not be a viable choice for communities that are not looking to commercialize their Traditional Cultural Expressions. Secondly, Geographical Indication may be a viable choice for communities who are into art and crafts, but protection of dances and music are not catered by this kind of IP. Third and the most crucial aspect is, even if a person outside the community gets a license under the Geographical Indication, they cannot possibly oversee the quality of art that they are sending out to the consumers. And, this would inherently dilute the distinctive nature of Traditional Cultural Expressions.

Is there a solution?

Many scholars and researchers, over the years, have opined that there is a requirement for cultural protection. A cultural protection would entail a unique set of rules and regulations. The rules may resemble a privacy policy sort wherein, the practices are concealed in a way that non-indigenous people are bound to take permission from the respective community. However, this method may not apply retrospectively and will obviously require input from the indigenous population.

The need of the hour is to relook at Traditional Cultural Expressions, understand them not from a modern perspective but from a different lens for which assistance can be sought from libraries, archives, and of course indigenous people themselves. For now, the only step towards protecting Traditional Cultural Expressions can be taken is to acknowledge their work and not take credit. Further, if possible, engage artisans from the indigenous communities and give them a platform to take ownership of their work. Lastly and more importantly, do not exploit communities of their work, as it is never ours to claim or make profit from.

Let us be better for the indigenous community and protect their rights, even if the law doesn’t!

…

Niharika Malhotra is a practising advocate, specialising in Intellectual Property rights. She has a masters’ degree in IP, from The George Washington University and has completed her fellowship from the Wikimedia Foundation, the operator of Wikipedia. She runs The IP Edit, a social media platform that dispenses general information and advisory on IP rights and is a voice for the rights of the indigenous community.

Niharika Malhotra is a practising advocate, specialising in Intellectual Property rights. She has a masters’ degree in IP, from The George Washington University and has completed her fellowship from the Wikimedia Foundation, the operator of Wikipedia. She runs The IP Edit, a social media platform that dispenses general information and advisory on IP rights and is a voice for the rights of the indigenous community.