About a year ago, my husband was looking for some formal wear. For quite some time, now, his go-to brands have been H&M and Marks & Spencers. Well, not this time, if I can help it, I decided. If we had to buy any new clothes, it was only going to be from homegrown, ethical brands. And so, I took on a long, arduous search for a brand that would cater to his needs. There were a few things that struck me:

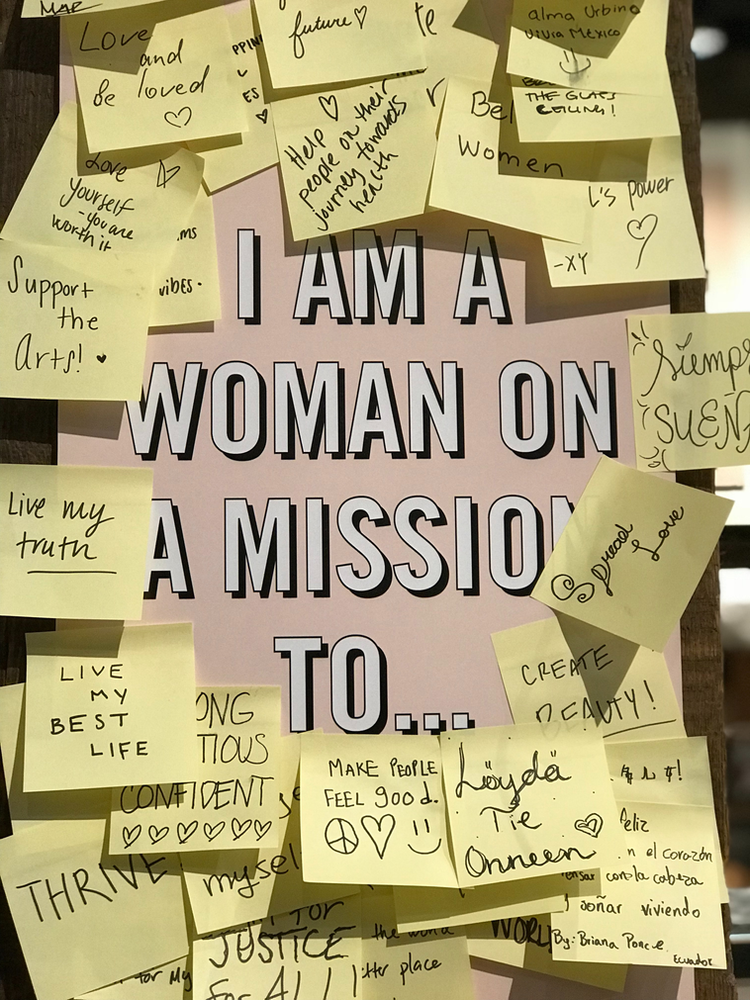

1. Most ‘conscious’ brands are run by women.

2. Irrespective of who they are run by, the majority of them target women consumers.

3. Most of them are not as selective about the artisans they work with.

4. Why was I looking for brands for him to buy from?

The term ecofeminism was coined by French feminist Françoise d’Eaubonne, in 1974. It is defined as the intersection of gender and climate change. For decades, now, the ecofeminist movement has tried to highlight how climate change inequitably impacts women, due to inherent economic biases as well as women’s traditional roles, as deemed by the patriarchy. The ideology argues that the treatment meted out to women and the degradation of the environment are twin effects of the patriarchy, on the one hand, and of capitalism, on the other.

In the 1990s, the idea began to be dismissed by many intellectuals as it seemed to oversimplify complex societal hierarchical structures as well as geographical and social locations, including race and class.

There was also the concern among many that a subsect of ecofeminism, called cultural ecofeminism, which spoke of the intimate relationship between women and the environment, only served to reinforce existing gender roles, biases and stereotypes, therefore leading to internalising and even romanticising the exploitation.

However, over the last decade, with intersectional feminism gaining momentum, the conversation is coming back into focus. In her 2014 book, Ecofeminism, activist Vandana Shiva talks about the marginalisation of women in the global South (i.e. developing countries) due to loss of local biodiversity, in the aftermath of colonialism and due to continued exploitation through capitalism and monoculture (the cultivation of a single kind of crop, which is as far removed from agricultural best practices, as can be!). She argues that these systems have alienated women from their roots and the skills they know best, removing them from the decision-making and reducing them to unskilled labour. Their work, due to its cyclic nature, is also being taken over by biotechnology and other tech. As a fall out, women are generally the first to lose their jobs in times of crises, such as the recent pandemic. According to Earth.org, women are 14 times more likely to die from a climate change-related disaster as well as suffer disproportionately from related resource depletion and poverty.

But what does all of this have to do with my husband’s formal wear? Well, nothing and everything. The fashion industry is one of the largest employers of women, at every level of production, but especially at the grassroots. A staggering majority of textile and garment workers are women. Traditionally, women were also the skilled artisans, but over time, their work has been taken over by their menfolk. Most ‘conscious’ brands that ‘handcraft’ their clothing are only serving to further this divide, by continuing to work with male artisans instead of empowering women artisans.

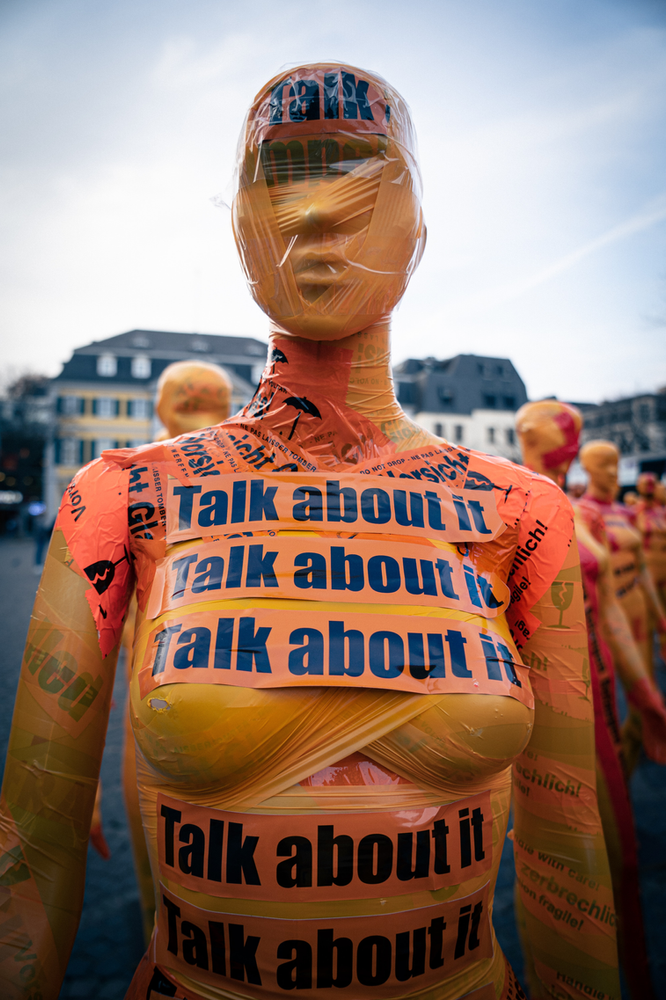

According to a 2021 study, published in Energy Research & Social Sciences, 66% of climate activists under the age 25 and 55% between the ages of 25 and 35, are women. The data was collected from 66 countries! With the conversation around sustainability catching on, there is also the concern voiced by many that the greener options available in the market today, are skewed towards products for women. From sustainable menstruation to body care, there are plenty of measures available to women, to lead a greener life, but little for men. Take any sustainable fashion brand, too. Barring a few options for casual shirts and kurtas, there is little choice for men, while can pick the gamut, from fun dresses to occasion wear. Even active wear, footwear and accessories. But men simply don’t seem to be a market. The fact that most ethical brands are being championed by women is telling, too.

Australian ecofeminist Ariel Salleh focuses on the magnitude of women’s work, the nature of that work and the exploitation of women’s labour, globally. A quick look at the #PayUp campaign, throws some alarming figures that back this up. A major fashion brand that has owed 2,000 female garment workers wages to the tune of $5.5 million, signed up a famous male sportsperson as a brand ambassador for a whopping $300 million! There is also the issue of female garment workers earning poverty wages being subjected to gender-based violence at the hands of their well-paid male supervisors.

It’s easy to say that we need to break this cycle. But how? Sure, what we really need is more systemic change. But we can’t wait on that forever. A good starting point is for homegrown brands to diversify. For them to look closer at who they are catering to, and who they are empowering. While the idea of women-led brands is empowering, if these brands are only going to widen the gap between male and female artisans, and play into the stereotype of women as primary shoppers, how mindful are they, really?