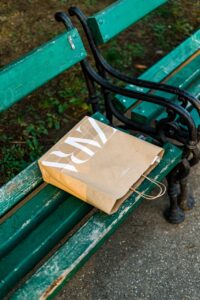

On 20th October, fast fashion giant Zara announced its entry into resale and repair, with Zara Pre-Owned. The programme, which launches on the 3rd of November, aims to enable shoppers to repair damaged items or get rid of unwanted items, through an online booking service or in-store.

While this is definitely an interesting move towards a more circular business model, is it really going to take a brand that has long symbolised everything that’s wrong with the fashion industry, and turn it into a beacon of sustainability? Secondhand, in itself, has its pros and cons. And as we have seen in the case of Levi’s, it isn’t a guarantee of a brand’s sustainability, either. So when fast fashion brands like Zara and Shein launch resale programmes, what does that really mean? We broke this down, in the context of Zara and its entry into resale.

You can get your clothes repaired

The not-so-pretty:

Story time! Many years ago, I wore a Zara jumpsuit to lunch at a restaurant in a mall. The jumpsuit was fairly new, worn only twice. Somewhere in the middle of a morsel, I realised I had a rip along the side of the leg. As soon as I wrapped up lunch, I walked down to the Zara store, at the other end of the mall, to complain. They gave me a change, took my jumpsuit, and asked me to wait a bit. Ten minutes later, I had a repaired jumpsuit, with reinforced stitches. No extra charge.

The reason my jumpsuit had ripped so easily was poor quality production, something I’d obviously failed to check while buying. The garment had only a single stitch running along its edges, with zero margin. So when it ripped, I had a gaping hole, up my thigh, and the hole just kept getting bigger. Also, not surprising, given the scales Zara produces at, the turnaround time they give the garment workers, and how much they pay them.

The Zara Pre-Owned repair service is not a warranty service. It isn’t a way to ensure Zara produces better quality garments, which will last longer. And it isn’t like you call customer service or walk into a store, tell them something ripped, and it will be fixed free of cost, like it happened for me. If anything, it now gives the brand a streamlined way of monetizing a service they did, in fact offer anyway, just not in a formalised manner. In case you hadn’t noticed, most stores have in-house tailors to offer minor nips and tucks, for better fitting, especially for men’s trousers.

The pretty:

Clothes with an inherently short life-cycle get a longer lease of life. Just like my jumpsuit. I took a chance, when I walked into the store. I didn’t have the invoice and the dress had been worn, so I knew an exchange or return was completely off the table. But I hadn’t anticipated a repair, either. My best case scenario was, I’d walk in, make a noise, they’d apologise, and that’d be that. But now, if you’re in a similar situation, you know exactly what to expect, albeit for a charge.

Zara offering repair services also represents a shift in mindset. ‘Given the influence a brand like Zara has over consumers, I would celebrate them offering repair services,’ says Shruti Singh, Country Head, Fashion Revolution India. ‘I believe it would be really good for changing consumer behaviour and perception, and will make repairing cool.’

You can donate your clothes through Zara

The not-so-pretty:

Zara first introduced donation bins across stores in Europe, in 2016. They subsequently also introduced a mail-in system for donations. Shortly before the pandemic, Zara introduced collection bins across select stores in India, in a model similar to H&M’s: Clothes that are perfectly wearable are sent for donation, while clothes made from non-blended materials are sent for recycling. But as has recently come to light, less than one percent of the clothing sent for recycling is actually recycled. The story is similar for donations, too. Most fast fashion sent for recycling or donation ends up in Kantamanto Market, Ghana, or the Atacama Desert, Chile, or even in landfill.

The pretty:

Zara’s donations bins are not exclusively for Zara clothing. Or at least that has been the case so far, which is a good thing for consumers hoping for a more responsible way to dispose of their unwanted clothes—whatever the truth may be. However, Zara hasn’t yet put out enough information on how the new system, which they describe as a ‘peer-to-peer platform’, will be different from the existing model. Whether it will be able to address the aforementioned deficits, is something we’ll have to just wait and watch.

You can sell and buy secondhand

The not-so-pretty:

When juxtaposed against zero conversations around degrowth, and changes in Zara’s production systems, resale feeds into consumerism, rather than slow it down. Industry experts warn, this may also increase the disposability of clothes, because when people believe the product they are buying will have a second life, the primary purchase becomes ‘a purchase with no consequence’. Essentially, it becomes OK to buy something you’ll wear to that one occasion, because disposal is so much easier and, at least in theory, more responsible. According to a report by The RealReal, consumers are turning to thrifting and resale as an alternative to fast fashion, buying and selling secondhand goods a lightning speed. Without the brand improving the quality of their clothing, slowing down their production and paying better wages, this is less sustainability, more greenwashing.

The pretty:

With this one step, Zara have officially—and effectively—taken charge of their resales, which were, up until now, a third party function. Given how integral Zara is to consumer culture, it’s a common feature on resale platforms, too. By reclaiming the sales, the brand has made a solid move to own its secondhand market, in itself a good thing. When a retailer takes charge of the brand’s resale, secondhand buyers can be assured verified products. Given Zara’s influence on consumer culture, it also helps the conversation around resale, secondhand and preloved gain momentum.

‘It’s a great first step, I would say, but till we know more about how it’s going to affect their first production cycles, we’ll just have to wait and watch,’ says Singh.